It’s 7 A.M. on Columbus Day, and the block-square gray mass of city hall on LaSalle Street is battened down for the holiday. “City Hall is Closed” reads a sign hanging on the main doors. Inside, deep in the marble gloaming, a pair of Chicago police officers is chatting and apparently ignoring this writer, the out-of-town visitor with an appointment at the mayor’s office trying all the locks. Finally, I find the single unlocked door and step inside.

Five floors up, light leaks into a dark hallway from the sage green lobby of the Chicago mayor’s office. One wall is covered with a perfect rectangle of 45 framed black-and-white portraits of all the men—and one woman—who’ve led Chicago. Well, almost all of them. Current mayor Rahm Emanuel isn’t there; neither is his immediate predecessor, Richie Daley, who held the job for 22 years. A police officer says it’s because no one has yet figured out how to rearrange that symmetrical grid and add them in.

There’s also been more pressing business in the mayor’s office lately. Like balancing a budget for a city that’s $750 million in the hole. Like hosting NATO in full security lockdown. Like wrangling with the striking teachers union, the third largest in the nation. And like creating partnerships with corporate America. That’s what happening here this morning. A gaggle of corporate bigwigs is gathered around a TV—they’re the three CEOs from the major soft-drink companies, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Dr Pepper Snapple Group.

Their eyes are all fixed on Morning Joe, in which Mayor Emanuel and Susan K. Neely, the CEO of the American Beverage Association, arebeing patched in from Chicago via studio remote to talk to Joe’s Mika Brzezinski and Mike Barnicle in New York City.

The mayor is on the air to announce that Chicago city employees (and their spouses) are in a health and weightloss competition with their counterparts in San Antonio, Texas. The contest is sponsored by the American Beverage Association, which will pony up $5 million to the winning city. Emanuel is crowing that 38,000 Chicago employees have already signed up, but the Morning Joe anchors aren’t so interested. They want Rahmbo, as practically everyone in politics still calls him, to comment on the disastrous showing by President Barack Obama in the recent first debate. Emanuel is, after all, Obama’s former chief of staff and former campaign cochair and is now actively involved in a super-PAC raising money for the president’s reelection.

“The 38,000 participants in Chicago’s wellness program, municipal employees, is it mandatory they join?” asks Barnicle. “The second part is the 38,000—is that number approximately close to the number [of calls] you received from horrified Democrats like me wondering what happened in the debate?”

In his brief time on the job, Emanuel has faced

In his brief time on the job, Emanuel has faced

a city in debt and a teacher’s strike.

Photo: Brooke E. Collins/City of Chicago

Old Rahmbo might have snapped up that bait and seized a moment on national TV to yank and spin it hard. But the new Rahm? Mayor Emanuel of Chicago? Not going there.

“Competition is our middle name,” he says with a smirk.

“Yeah, especially Rahm’s,” Brzezinski responds. “The companies that are on your board are very much part of the obesity crisis because people drink too much of them. That’s fair to put on the table, right?”

Rahmbo remains on message. He smiles, a rubbery grin that’s mostly Joker with a hint of teddy bear. He won’t get mad. But he just might get even.

Just outside the room where the CEOs are watching television, the city hall press corps is reporting for duty. Columbus Day is a reliably slow news day that once would have required them to do nothing more than follow the mayor and other city pols as they gladhanded parading Italian-Americans.

That’s not happening this morning. Reporters slide into their seats, grumbling. It’s a holiday, for chrissakes! “Not for this mayor,” one writer snaps. Jokes are made about how Emanuel may be “alienating Italians” by not marching in the parade.

Then movement. Nine TV cameras zoom in; newspaper and radio reporters simultaneously click on their digital recorders. A door behind the podium swings open, and out comes the 52-year-old Emanuel, all 5 feet 7 inches of him, in a navy suit, leading the soda CEOs. The reporters listen as the execs and Emanuel speak about the competition. The first thing you notice about the mayor is that he likes to talk in numbered lists, even if the ideas he’s listing don’t always flow logically into one another.

“If you put aside personal responsibility, you are missing the core ingredient from improving health-care outcomes,” he says. “Since I believe in personal responsibility, and this is one of the key ingredients to improving outcomes and controlling health-care costs, then you have a campaign built on that premise. One, you get a cash bonus, and the cities get a cash bonus too. Two, we have 80 percent participation in our employee wellness program. Nobody else has that. And three, lastly, if you participate, all you have to do is try. Look, all you have to do is try! You don’t have to get a result. If you do that, you are financially held harmless.”

Now it’s question time. Veteran city hall correspondent Fran Spielman pipes up with the first one, which is rhetorical: “Obviously, what’s in it for the beverage industry is to avoid what New York did with the Big Gulp ban and the sugar tax here in Chicago.”

Rahm cedes that query to beverage association head Neely, in heels and a blazing orange ice-skater-ish dress, who stands at least a head taller than the mayor and who’s been chomping at the bit.

“This industry is about leadership!” she punts. “We believe that there is an obesity challenge in this country, and we have been on the record doing meaningful things for many years now.” She rattles off a round of statistics about how “study after study” has shown that “discriminatory taxes don’t change behavior.”

The mayor waits, then steps in. He oozes reason, while occasionally stumbling over his sentences—a tic he shares with almost every other Chicago mayor in recent memory.

“Fran, I would just say, look, the country as a whole, our city, we have, which is why Michelle Obama has focused appropriately on obesity, we have a problem, and kids are now developing type 2 diabetes. We have to come up with strategies to deal with it. I believe firmly in personal responsibility. I believe in competition, and I believe in cash rewards for people who make progress managing their health care. If they make progress, city taxpayers will also make progress.”

He takes a few more questions and uses the opportunity to extol his city employee wellness program, a voluntary program that requires people to lose weight and make preventive healthcare changes. They can fail, he insists, but they just have to try. And if they don’t try, well, their co-pays will go up.

“Why should anyone sign up if they risk their co-pay going up?” asks a reporter.

Rahm’s got an answer to that. Sort of. “You should take note that they know that, and still we got 80 percent participation.”

Asking him about the issues of the day is the reporters’ job. But Emanuel seems to view answering them, though, as not necessarily being in his job description. Sometimes, when he bounds into a press conference, he’ll gleefully quote Henry Kissinger: “Anybody got questions for my answers?” The newshounds are, of course, wise to his wriggling. One city hall scribe says, “Daley used to use us more to get his message out, but this mayor thinks it’s his job to manipulate us.”

Outside, downtown Chicago’s skyline sparkles under a gorgeous autumn sky. This isn’t the Chicago of stockyards and corned beef and broad shoulders, and it hasn’t been for a while. It’s cutting-edge chef Grant Achatz’s Chicago, gleaming Millennium Park Chicago, a city of triathletes (the mayor is one) and lakefront cyclists. At least, that’s the view looking north. To the south, there are nearly 150 public schools without libraries and a recordhigh murder rate in the poor neighborhoods.

Politically, it’s a new era too. Before Emanuel was sworn in on May 16, 2011, the city had been run by a dynasty of Daleys for five decades, with an interregnum in the 1970s and 1980s. The city survived the epic decline of the urban Rust Belt due to its great economic diversity—no sector of employment is greater than 13 percent of the total. Along the way, the Windy City matured, entered the new century and left behind some treasured traditions. One change, initiated just before Emanuel arrived, is that there’s no downtown Columbus Day parade. All the floats and streamers, baton twirlers, marching bands, oldworld maids dancing the tarantella and elderly men with red-white-and-green Italian flag sashes are mustering on a street way out of sight of city hall.

Rahm Emanuel, then the general manager of the Clinton Presidential Inauguration Committee, outside the Capitol in December 1992.

Rahm Emanuel, then the general manager of the Clinton Presidential Inauguration Committee, outside the Capitol in December 1992.

Photo: Marianne Barcellona/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

New Chicago—yuppie, ethnic, prosperous but still no bullshit—is Emanuel’s town. He lived here until fourth grade, when his family moved north to the suburb of Wilmette. Born to an Israeli father and a mother whose parents escaped from Romania before World War II, he has two brothers and a sister. All three Emanuel boys grew up to be wildly successful. Younger brother Ari is a powerful Hollywood agent who inspired the crass, hyperactive dealmaker who was played by Jeremy Piven on HBO’s Entourage. Older brother Ezekiel is an oncologist and bioethicist at the National Institutes of Health.

And middle brother Rahm is mayor, of course. It’s a job he says he’s had his eye on for a long time, although he’s taken a circuitous road getting there. He studied ballet and performed with the dance troupe at Sarah Lawrence College, where he got a degree in liberal arts. During the Gulf War he spent two weeks in the Israeli army, repairing trucks. He returned to school to get a master’s in speech and communication at Northwestern and then became involved in Illinois politics, fundraising for local campaigns. He worked on Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign, which led to a position as a White House senior adviser. In 1998 he quit politics to join the private sector and work at investment banking firm Wasserstein Perella—where he made $18 million.

Still, he couldn’t stay away. In 2002 he ran for a Congressional seat and was elected, representing Illinois’ fifth district through 2008 and rising to the fourth-highest Democratic post in the House (as chair of the caucus). Although he initially supported Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid, he endorsed Barack Obama, then a senator from his home state, after the Democratic primaries were over. He was rewarded with the plum but stressful position of White House chief of staff, which he held from 2009 through most of 2010, when he resigned to move back to Chicago and run for mayor.

Senior presidential adviser Emanuel with presidential aide Stephen Goodin, White House chief of staff Erskine Bowles and President Bill Clinton in the Rose Garden in June 1997. Photo: Getty Images

Senior presidential adviser Emanuel with presidential aide Stephen Goodin, White House chief of staff Erskine Bowles and President Bill Clinton in the Rose Garden in June 1997. Photo: Getty Images

His early dance training has served him well in posture and politics. He’s a lithe, high energy guy with a ramrod-straight back who bounds and prances more than he walks. In Washington he developed a reputation for his theatrical gestures: sending a rotten fish in the mail to an errant pollster, repeatedly stabbing a knife into a dinner table the night Clinton was elected in 1992 and declaring that his enemies were “dead!” and warning British prime minister Tony Blair, before an appearance with Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky affair, with the ominous words “Don’t f–k it up.” Then there are the countless episodes of him screaming obscenities at reporters and browbeating wayward congressional representatives and donors, which, depending on what side you’re on, have earned him love, respect or enmity.

No U.S. mayor today—or probably ever—can boast that he or she learned the art and craft of politics and governing at the side of two presidents. For Emanuel, it was an invaluable education. “Let me say, I don’t think I would even know how I would be mayor if I hadn’t had the opportunity to work with Presidents Clinton and Obama,” he says. “They gave me a depth of experience, an ability to think strategically about policy and politics around that. Two, it helps me think through little things.”

He said what he took away from Obama was how to present an argument like a lawyer; from Clinton he learned how to make it folksy. “President Obama is appropriately linear in his knowledge of presenting an argument, almost like you are going to court. And President Clinton has a way of posturing something that is complicated but accessible to people. And even as I draft this [budget] speech, it’s helping. I always say about politics, people hate the status quo. Well, they’re not too excited about change either. How do you get people to make change where they don’t think they’re losing? That’s something I learned from both President Clinton and President Obama.”

An hour after the press conference, two black Chevy Tahoes idle outside city hall. One is for the mayor, and the other is for the reporters going to the next event, a public unveiling of an overhauled mass transit station. Emanuel gets into one of the vehicles, a burly bodyguard with an earpiece climbs in, and we roll. We’re headed uptown to the refinished elevated (El) stop at Argyle Street, smack in the heart of a Vietnamese community.

In the chilly lakefront breeze, the mayor greets commuters and meets up with Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky. The two pose with a gaggle of Vietnamese business owners and yellow hard hats for a photo op. Then he heads downtown to a lunch with Italian-American business leaders—it is, after all, Columbus Day—at a baroque red sauce and chicken Vesuvio palace called Italian Village, complete with miniature bubbling Trevi fountains and dessert carts groaning beneath panna cotta and tiramisu.

Finally, at two in the afternoon, he’s able to stop and sit down with me for an interview. He’s been up since five, then exercised for two hours before the Morning Joe spot. The mayor tries to work out one to two hours a day.

He welcomes me into his spotless office (he is a notorious neat freak). The furniture—a gray couch and a pair of sleek wood, chrome and leather armchairs—is locally designed and manufactured. The only antique is his vast wooden desk, which was once used by Mayor Anton Cermak, who was assassinated in 1933. There was no special reason for selecting it out of the city warehouse, Emanuel says. He just liked the way it looked.

Two mementos on the walls are from his most prominent mentors: a handwritten to-do list by President Obama and a signed photo of President Clinton. Another wall is covered with a rotating display of work from students at the Art Institute of Chicago. He also has a few pieces borrowed from the Art Institute and the Museum of Contemporary Art, including Seymour Rosofsky’s late-1950s oil painting “Unemployment Agency” and Leon Golub’s “Head II” from 1959.

Up close, he’s shorter than you’d think and even more intense. Proudly, unrestrainedly nasal and pitched a bit high, he speed-talks in the clipped, sometimes garbled shorthand of a man used to sound bites and shouting orders.

“This is the best job I’ve ever had, public or private sector,” he says. “It’s my dream job, and I love it. You actually can do things.”

He starts ticking off those things: making the school day longer and affecting the lives and futures of 400,000 kids, working with big pharmacy chains to put fresh-food aisles in stores in so-called food deserts and building new boathouses and walkways along the historically industrial Chicago River. “You will be able to walk along the water like a boulevard. Where else can you change an entire landscape?”

He talks about spending Saturdays at Target, “just talking to people,” which he calls Target town halls, and taking the El to work at least once a week to rub shoulders with Chicagoans.

“It’s a hands-on, roll-up-your-sleeves, make-a-difference job. In addition, and I say this affirmatively now, if you like politics and you like policy and you like the intersection between those two, this is a government closest to what and how people live their lives.” A journalist who recently profiled him described how J Crew stores had replaced slag heaps, warehouses and taverns in the city. I ask him if he’s a new sort of J Crew mayor for Chicago. He said he was happy to provide a fashion metaphor, but first he needed to get a few things off his chest.

White House chief of staff Emanuel with President Barack Obama in the Oval Office in January 2009

White House chief of staff Emanuel with President Barack Obama in the Oval Office in January 2009

Photo: Getty Images

“Let me take two steps back and talk about why I also want to do this job,” he says.

“My view is when we grew up around politics, we grew up with the all-powerful nationstate. Now I don’t have an Iran [pronounced eye-ran] policy, and I don’t want one. But if you look around the world now, I actually think this is going to be the century of the city. There are about 100 cities in the world that are the economic, cultural and intellectual energy of the world today. Chicago is one of those cities. Look around the world and look at this time. The cities are Paris, Berlin, London, Chicago, Shanghai, Rio, New York. There’s no guarantee that 20 years from now Chicago’s here. Nothing is certain. So what you do today determines whether it’s a viable city. What I do today as mayor—attract talent, build industry, strengthen our schools, support our businesses, expand our broadband and the rail—determines whether the city of Chicago stays on the level of Shanghai and New York and London.”

Another pet project of his is creating what he’s calling a “digital alley” on a stretch along the river that once housed the great department stores and showrooms of the last century. Now Google has offices in the massive Merchandise Mart (one of the biggest commercial buildings in the United States), a behemoth that still houses thousands of furniture showrooms, and Groupon is in the old Montgomery Ward building. All told, there are 7,000 digital employees working at more than 200 companies. Motorola will soon be bringing 3,000 employees to the area as well.

“Rahm is strategic and innovative in his thinking—he is a great partner to work with,” says Brad Keywell, a Chicago entrepreneur who, among other ventures, is cofounder and director of Groupon. “His ability to collaborate with leaders from across all fields—technology, finance, health and education—make him an incredibly creative mayor and will ensure Chicago remains a world-class city where business and families can thrive.”

Emanuel is striving to transform a slice of old Chicago into something sleek and young, like a Midwestern Seattle. His office has been deeply involved in creating a tech incubator in 50,000 square feet in the Merchandise Mart, where entrepreneurs can work, get free advice and meet with accelerators and potential investors. The site is named 1871, after the year of the great Chicago fire, to commemorate the spirit embodied in Chi-Town’s rise from the ashes.

Emanuel claims he is the first Chicago mayor to go downstate to the engineering and computer-science schools at the University of Illinois at Champaign to keep young tech talent from departing. “All these kids getting paid by the state leave!” he says. “You give me three years, every graduate of the University of Illinois, and I will get you five new companies that will be on the stock exchange in four years. We will keep them.”

He ticks off yet another list of the incentives that will entice them. “One, great nightlife; two, bike lanes; three, a great mass-transit system; four, Lollapalooza. We are doing a whole recruitment around that. Tonight the Big Ten schools are all invited to Chicago Ideas Week. We pay for their stays, the private sector does.”

While Emanuel, like other mayors in the era of empty public tills, is a staunch proponent of private-public partnerships, his relations with the corporate class have become a rallying cry for progressives who oppose him. Two local reporters examined the mayor’s meeting schedule for the first year in office and concluded that Emanuel’s precious face time was doled out liberally to people with money and sparingly to community organizers and groups with little in campaign funds to offer.

Another major criticism of Emanuel has been of his bulldozer governing style. Less than five months after being sworn in, he fired the ethics board and replaced it with his own people. In May, he oversaw a city lockdown during NATO, with many protesters arrested in what activists charged were civil-rights infringements. Most recently, the day after we met, he presented his second budget without any public comment hearings, which Daley, his predecessor, had always held. Emanuel’s move provoked some aldermen to offer their own public comment sessions.

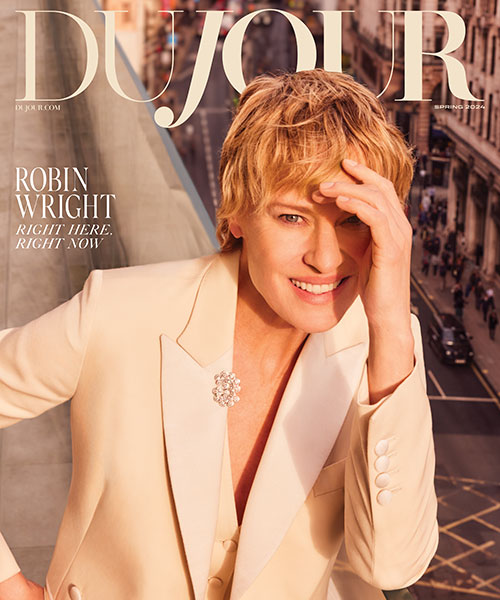

Rahm Emanuel and wife Amy Rule with daughters Leah and Ilana

Rahm Emanuel and wife Amy Rule with daughters Leah and Ilana

in Chicago on election night in February 2011.

Photo: Getty Images

“For an administration that has pledged transparency and an open process, they have shut out the public and the taxpayers and other shareholders,” progressive alderman Bob Fioretti said to radio station WBEZ. “The people deserve a voice, and we as aldermen will fill the void and the failure of the administration.”

Emanuel’s aversion to public hearings might have been cemented by a traumatic day during his mayoral run when he had to suffer a day-long public hearing on his residency in which he was excoriated by a theater full of cranks, ranters, anarchists, politicians, concerned parents and a random array of Chicagoans, all of whom had the right to stand and speak. (While Emanuel was in Washington, he rented out his Chicago home, and he claimed that his wife’s wedding dress and baby photos of his three kids in the basement were proof enough that he was a city resident.)

His apparent aversion to mixing with the masses—and the NATO arrests—prompted Rolling Stone writer Rick Perlstein to write that “Rahm is no friend to democracy.” So I ask, “Are you the guy they call King Rahm?”

He gives a dry, slightly annoyed laugh, leans in and says, “I just gave you a description of why I like this job. I don’t have to walk around and do Target town halls. I have run for five elections, where you have to go out and meet people. I did 110 El stops, countless groceries. And I still take the El and still go to grocery stores. I don’t have to do it.”

Besides the King Rahm–ness, some Chicagoans I met (full disclosure: it’s my hometown, and I have many family members and friends there) complained that their mayor was a tad tense and humorless. For a politician, he’s definitely not one for small talk.

“Sometimes I jokingly I say I wish I was a mayor during the Nineties,” he says, with a braying hahahahahaha. His exclamation is not a laugh so much as an intake of breath to fuel what’s coming.

“That said, this year we will be able to balance the budget, not raise taxes or fees, invest in early childhood education classes for kids, summer jobs, doubling the size, pre-K to 5,000 more children, add to our police force, invest in basic services like rodent control and tree trimming and all that and do some stuff on small business. My view is, yes, these times can be challenging, but challenges are a time for creativity. To use a phrase I used to use with regularity: Never allow a good crisis go to waste. It’s an opportunity to do things you never thought you could do. In my last budget, my first budget—not King Rahm, we passed it 50 to zero. We did close to 14 things that had been discussed. Simple things. Take garbage away from ward committeemen [oversight] and put it on a grid model, like FedEx and UPS, saving $20 million just doing a few less right turns by trucks. We debated that for 10 years. Done! Nonprofits like Northwestern University and Shedd Aquarium used to get free water. Not now. Done!”

He slows down to let his brain catch up with his words. “Can you do everything? No. But Chicago is a city that dreams big, and to do those things you have to be creative. Nobody wants to make changes just so I can buy more gravel for the deficit hole!”

Emanuel may be staying on message these days, but he’s still known to let an F bomb fly. Old habits die hard. His greatest challenge so far—and maybe his worst moment—came in September, when 90 percent of the Chicago Teachers Union voted to strike, leaving parents and kids scrambling. The breakdown that led up to the seven-day-long strike was brutal, and the mayor emerged from those final talks literally shaking with rage. About those discussions, Chicago Teachers Union president Karen Lewis later described him as “a dirty, low-down street fighter.”

Emanuel with kids in Chicago in October 2011.

Emanuel with kids in Chicago in October 2011.

Photo: Getty Images

Once he might have relished that epithet. Now Emanuel is more concerned with the politic side of politics.

“Well, I did fight for the kids of the city of Chicago,” he says. “They had been shortchanged with the short school day. This has been a decade-long discussion, why Chicago had the shortest school day in the nation of any big city. Nobody in those discussions had ever gone to school on that short day. And nobody can tell me that’s good for kids. I made a pledge when I ran to get done for the kids what had not been done for a decade. It was being negotiated between adults, not on behalf of kids, but for themselves! I am very proud that I have given principals, teachers, parents and kids the ability not to choose between math and music, but to do both; not to choose between algebra and arts, but to do both; not to choose between reading and recess, but to do both. So people can say whatever they want about me, but I know one thing: Every first-grader today that graduates high school gets two and a half years more in the classroom. And that’s a good thing. You can describe it any way you want, but I see it as one thing: keeping my word.”

The jury is still out on who won and who lost in the strike. The teachers went back to work, and Emanuel got his longer days, but the teachers beat back his effort to make test scores the main factor in evaluating their performance. Emanuel’s handling won him kudos from one quarter: U.S. mayors. The night we met, Emanuel joined three other mayors and a moderator at the opening night of Chicago Ideas Week, a sort of Midwestern TED talk series. Much of the panel discussion focused on how to run cities in lean times and, especially, what to do about education.

Mayor Michael A. Nutter of Philadelphia praised his Chicago host’s handling of the schools crisis. “We’ve all learned a lot from Rahm, saying this is what I am trying to accomplish and this is what I am about. As adults, we sometimes forget what this system was created for. It was created for children, and we need to keep the focus on what’s best for children and not what’s best for adults.”

Some of Emanuel’s greatest fans are those who forged friendships with him during crises in Washington. Dee Dee Myers, the former White House press secretary for President Clinton, is one of them. She sees a man who’s matured along the way.

“When he came to Washington with President Clinton, he was already a star, a guy could get things done. He ran the finance operation during the campaign, and he ran the inaugural. Both were big successes. And once he got to the White House, if the president asked him to take the Hill, he’d take the Hill. But a lot of times he left a few bodies, or at least a few bruised egos, along the side of the road, and it didn’t always serve him or the president well. He got moved out of his job as political director after just a few months, when he offended one too many Democrats on the Hill. But he worked incredibly hard to make it up to both the president and the first lady in the months that followed, and the results speak for themselves.”

She continued, “In the past 20 years, as a member of Congress, as White House chief of staff and now as mayor, he’s learned to bring people along, to make allies on the road to making progress. That’s not to say he doesn’t still ruffle feathers. He does. Just ask the leadership of the Chicago Teachers Union. But he also makes friends, builds coalitions, looks for consensus. He’s results-oriented and a better listener than people who don’t know him might think. He’s also incredibly loyal. In a country where there just aren’t that many big, compelling political personalities anymore, he’s one of them.”

Since he spent the morning talking about personal responsibility, I wanted to ask the mayor to share his own lessons in the area. Emanuel and his wife, Amy Rule, have three children: Zachariah, 15; Ilana, 13; and Leah, 12. As a father, how does he teach personal responsibility?

“I won’t discuss it as a parent,” he says flatly. “I do believe in personal responsibility. I don’t believe you can get health-care costs down, plus people improving their health, if somebody’s not taking care of themselves. I don’t think there should be—and this may be philosophical—a government program to absolve people of responsibility. Now certain people, you and me, might be in different positions than other people. They might need more support, but you can’t build a whole culture absolving them of it.”

He goes off the record to describe a public-private partnership he’s crafting that should prompt more parents to show up at schools and pick up their children’s report cards.

“I’ll get you a full school day, I’ll get you good teachers and principals, but you gotta pick up your report card.”

I ask if he learned any lessons from the Clinton debacle in terms of personal responsibility versus self-indulgence. For a moment there’s a flash of the old Rahmbo.

Striking teachers on Michigan Avenue in Chicago in September 2012.

Striking teachers on Michigan Avenue in Chicago in September 2012.

Photo: Getty Images

“You know, I don’t think Clinton was a debacle,” he says. “He was a president who did great things, and the American people agree with me. His presidency was a landmark presidency. Both he and Obama will be seen as essential figures in changing the post-Vietnam Lyndon B. Johnson party.”

Clinton was impeached, I remind him. That seems like a debacle, right? Emanuel springs off the chair.

“That was a political act! Nothing to do with anything else. A political act by Tom DeLay and others to besmirch his character before the election, and they paid a price for it! Unlike any other president, his party won seats in the sixth year of his presidency, which broke a 100-year record, which says something about how the American people issued a verdict on the Republican strategy.”

Well, alrighty. I ask, “Clinton and Obama were mentors. Is either a political hero to you?”

“Look, I loved working with both presidents, who I consider friends of mine. Loved it. I am reading The Long Road to Antietam. I have probably read 30-some-odd books on Lincoln, not enough on Teddy Roosevelt, probably five or six on Jefferson.”

“And what about prior mayors?” I inquire.

“No disrespect to your profession—” he starts.

“None taken.”

“You haven’t heard what I’m gonna say yet,” he continues. “No disrespect, but those in it, trying to write history contemporaneously, they don’t have perspective. I remember vicious fights Richard J. Daley had building the University of Illinois at Chicago. Now you can’t even think of that community without it now. At the moment, you would have thought Chicago had this horrible autocratic mayor. Today? It’s the economic engine of the city. My view is I am not trying to step into anybody’s shoes. I’m trying to learn from other people’s experience. I didn’t come here to run for reelection. I came to make the change I promised happen. One more question.”

For the moment, Emanuel’s talked out.

“First Jewish president?”

“Not happening,” he says. “This is the last job in electoral politics, in public life.”

He stands up and bounds off in the direction of a back door I hadn’t noticed before.

“Legacy in 20 years?” I shout. “Or will you be mayor for life?”

“No. Not happening. Or won’t be married if so.”

With that he’s gone, a small man in a suit, moving fast.

Portrait of Rahm Emanuel: Jim Newberry